Crested Butte through Susan Anderton’s Drawings

Story by Dawne Belloise | Illustrations by Susan Anderton

Just off the south side of Elk Avenue on Third Street, where some of town’s art galleries are clustered, Susan Anderton’s work graces the walls of her Gallery 3 studio. There are colorful prints from her decades of designing the celebrated Flauschink posters as well as originals of local mountain scenery and wildflowers.

Some of the most intriguing work, especially for Old West architecture and history buffs or the merely curious, are the drawings of Crested Butte’s buildings that depict a simpler time back in the early 1970s.

There were then about 300 residents living in town, the streets were dirt and full of potholes, the buildings were dilapidated beyond rustic, and there were almost as many empty lots as there were structures. Every one of these drawings tells a story, as every house and building has its unique personality, captured in that moment and suspended in time.

There’s a haunting of time, a history passed into modernity, and it was fortunate for posterity and documentation that Susan captured the ambiance of the old Crested Butte through her drawings, exacting details that convey the real town as it once was 20 years after the Big Mine closed in 1952, well before tourism took the town beyond its original quaintness.

Hailing from Prestwich, England, Susan landed in Crested Butte in 1969 with her former husband, Cordley, an American she met in England and who decided he wanted to live in the mountains. They arrived in December and her first impression of the sleepy town was that she was visiting another world.

“It was hard to get here, but everyone was so friendly and welcoming. It was like going back in history, the old western town, the coal mining history, the families who had stayed when the mine closed, the old timers, some new, younger people of my generation, and a fledgling ski resort,” she recalled. Susan had arrived at the Denver airport and drove up at night, so she came into town after dark.

“I woke up the next day to this magnificent snow-covered landscape—it was magical. There were a lot of empty lots all up and down Elk Avenue in those days and very little development east of the Four-way Stop, just the old train depot and one or two houses. There was nothing at all south of Whiterock except the remnants of the coke ovens. Nothing north of Teocalli Avenue. There were no developments around Crested Butte, no Skyland, Riverbend, Riverland, no Crested Butte South, no Trappers Crossing. I thought it was magnificent, the vastness of the landscape and the mountains seemed endless to me.”

There was Stefanic’s for groceries, gas pumps at Tony’s and maybe three or four restaurants when she rolled into town. Susan had planned on being here for only six months but, she laughs, “It didn’t work out that way. We started a silk-screen business, Empire Tunnel Graphics, in the Company Store building. It was downstairs [for the first year], down a dark passageway, and we had a little room down there. We named it after an old mine.”

Susan thought the name appropriate with a tunnel for an entryway. She was one of many newcomers, young people, starting ventures in town, as a different demographic slowly began to catch wind of the funky little dusty town and breathe new life into Elk Avenue.

As Susan set up her life in Crested Butte, she was quite impressed with the more public and commercial buildings in town. “The larger buildings really stood out as being major landmarks because there was so little here.” She felt as though the buildings were framed by the empty lots around them. “They stood out as historic landmarks from the mining era. Some of them were dilapidated and run-down. Even without modern building methods, people could construct these large buildings back then and they took so much pride in the appearance of them. All the buildings have so much personality.” Susan was fascinated by the history of this town and the story of the old miners.

“The identity of the town was very much the old mining town, the mining and ranching families who had stayed after the Big Mine closed in 1952. It really was a glimpse into history, quite magical, an era I feel fortunate and privileged to have been here in time to experience. The buildings fascinated me because they were exactly as they had been during the mining days, and I set about drawing and recording them.

“I loved drawing Crested Butte,” Susan continues. “It was authentic, poignant, and heartbreakingly picturesque. Just walking down the alleys and having those glimpses,” she notes of the long-gone views, now blocked by newer buildings. “I was trying to get to the truth of what I was seeing here and not to gloss it up.”

Susan realized that change was inevitable in Crested Butte so she set out to capture its authenticity. She was prolific in her documentation; her drawings reflect the town as it was when she arrived. “Pen and ink seemed an appropriate medium to capture the detail and the texture of the buildings. To me, it’s a medium for telling a story because it’s illustrative. It seemed like the best way of really capturing the feeling of Crested Butte as it was in those days.” She started out with a drawing of Crested Butte Mountain as seen from the town in 1970 and her portfolio grew from there.

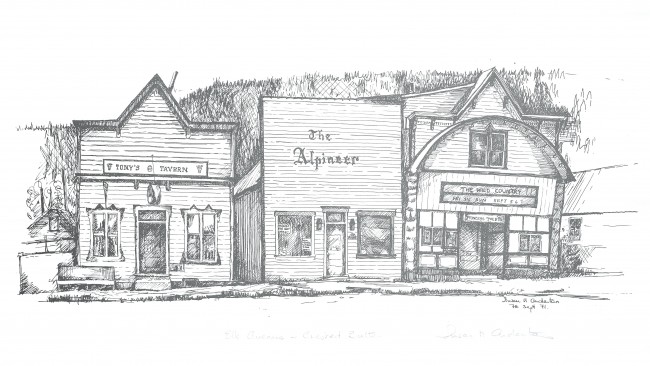

A sketch of three buildings on Elk Avenue shows the Princess Theater, the town’s movie theater at the time, now the Princess Wine Bar. With its wooden clapboard, the Alpineer stands within an arm’s length next to the Princess, the business having moved from the Company Store building in 1971. That building now houses Mountain Spirits liquor store. Next to the Alpineer in Susan’s drawing is Tony’s Tavern, now the Wooden Nickel, and she reconstructs the scene, saying, “It was Tony Kapushion’s place that was taken over by Don Bachman and was a 3.2 beer place. It had little booths and black and white checkered linoleum tile floor.”

Another drawing shows the Kochevar houses, built by Jacob Kochevar, Jr. and includes what Susan calls the 1913 Atchley House at the southwest end of Elk Avenue, still standing today. Notably, west of the 1913 building, there’s a rambling wooden structure with a front façade and a balcony connecting three buildings that was once a boarding house. It sags and stretches all the way back from Elk Avenue to what was known as the mink farm, where during the mining days, minks were raised for the skins.

“I had heard that the Kochevar houses were going to get torn down. There was a free store in part of it, with a huge pile of old clothing in the middle of the room and you could go in and sort through and take anything you wanted, or you could discard or donate clothing by throwing it on the pile,” Susan says of the shop utilized by the “hippie” newcomers. Across the street was a blue house named the Blues Project, owned by the Kahns. Susan drew the Kochevar buildings from the upstairs window of the Blues Project, which later burned down.

“I sat there for two entire afternoons to do the drawing. The Kochevar buildings were probably dangerous and a health hazard in their severe dilapidation, so the town decided they had to go,” she said. And a few days after Susan documented the building, it was torn down.

“They bulldozed the entire building, putting all the wood into a large pile, and like adding insult to injury, they had a large bonfire.” The 1913 building remains today, the date still easily seen on its rounded façade. Where the Kochevar houses were, another narrow building was erected.

Frank and Gal’s was also on Elk Avenue and Susan recalls, “It was a marvelous building with a beautiful bird’s-eye maple back bar. Frank and Gal Starika had an Italian restaurant and a bar, and Gal was famous for her spaghetti. Upstairs was a large dance hall where the town came to polka.” When Frank and Gal retired and sold the place, Susan did a drawing of the building and gave it to them as a gift. On Friday the 13th in December of 1974, the building burned to the ground. A few years later Susan had to redraw Frank and Gal’s since she hadn’t made copies of the original.

Susan recalls the conglomerate of shacks, buildings, barns, and a smoke house that made up the collective viewscape behind the current post office. She learned that the smoke houses were common for the old timers who would smoke their fish and game for preservation.

Many of those buildings are now gone—some were moved, some were demolished. Jim Barefield’s barn on Maroon is still standing, having been repurposed into his real estate office.

A peek through these spaces in 1974 shows there are no trees; in fact, there are very few trees throughout town.

The building that is now Izzy’s restaurant used to be on Elk Avenue next to the Grubstake building. It was originally a barber’s shop and later, in the 1960s, it was the downtown office for the ski resort real estate sales. In 1969, it transformed once again into a hand-carved sign shop by Barbara Kotz and later still, after an addition, it became the home for the Crested Butte Pilot. It was moved north, behind the post office to its current location.

In the alley between Maroon and Gothic and First and Second Streets is a shed, drawn in 1978 detail. Its structure was failing, the wood siding already falling from the frame, the window sashes gone and the metal roof in disarray with lopsided pieces hanging precariously above overgrown weeds. “It’s long since been rehabilitated,” Susan says, as have most of the back-alley buildings, remodeled and converted into garages, studios and residences.

The Company Store, now home to the Secret Stash, is Mission-Style Revival, with its stucco exterior and rounded front façade. Susan illustrates it in its simplicity. The building once housed and incubated many Crested Butte businesses after its initial function as the Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) main office where the coal miners got paid. There was a large safe, as well as a walk-in freezer to store ice and probably meats. The CF&I also owned the grocery store within, where the miner families would spend their paychecks on food and supplies. There was truth to the song “Sixteen Tons” that Tennessee Ernie Ford made popular early on, that claimed, “I sold my soul to the company store,” since families would often owe more for the items they bought than their paychecks would cover.

In addition to Susan’s print shop in the Company Store, Crested Butte’s only “mall,” there was Schmoozie’s Health Food; Tincup Tintypes, a Wild West costume photo portrait studio; Rags and Old Iron, a craft shop with pottery, crafts and sewing; Oh Be Joyful Pots to Pants, offering pottery and clothing; Guns and Smokes, a tobacco and ammunition store; The Basket of Light, “where there’s a candle for everyone;” Cinnamon Rainbow leather goods; God’s Eye Beads; CB Sports, ski equipment and accessories; High Country Sound, featuring records, tapes and stereo equipment; Red Lady’s Old Friends, “warm happy things glowing with age;” CB Notions, “gift items and all the things you need but forgot to pack;” Hecho a Mano, handmade Mexican clothing and crafts; Tailings bar and restaurant, and later Jokerville, a bar, restaurant and discotheque with “sandwiches, stew, chili and entertainment nightly;” and of course, The Washhouse, the only self-service laundry at the time where you “can’t beat the price.”

The arcade boasted “Interesting shopping in a friendly local atmosphere, opened daily from 8:30 a.m. to 6 p.m.” The entire former mall upstairs is now the Secret Stash Pizzeria and downstairs is the Red Room, a bar at night, shared in the daytime with Karma (also known as the Momo Man), and Chimi’s Nepalese food, and Wildflour Sweets baked goods.

On Second Street, the Slogar building, now home to a family-style fried chicken restaurant, was a neglected and empty building during Susan’s early days. The front-door glass and most of the windows were smashed and splintered, the siding worn and the foundation had failed. From her drawing, there appears to be a smoke house behind the building, or possibly an outhouse. Even the bushes and trees look downtrodden and unkempt.

The Croatian Hall, once the cultural center and lodge for the Slavic community, including dances, is on the corner and down the street from Slogar’s on Second Street. Susan tells that Second was an important street in the mining days with many bars and significant buildings because it was the route the miners took when returning home from a hard day of work in the Big Mine and they stopped into one of the many bars for a beer. The Croatian Hall now is home to Eleven’s Scarp Ridge Lodge.

Susan did hundreds of drawings, all capturing the essence of a sleepy town in unsuspected transition. Susan says, “Apart from the uniqueness of the old western town itself, I could not get over the magnificence of the setting, the spectacular panorama, the breath-taking variety of the skyline as one drops over the hill into town. I still can’t get over it! It is truly amazing. I have drawn and painted it many times and never feel I can do it justice.”